These are notes for a lecture given by AMA in a workshop about Responsible Research held at LMU in Munich (Germany) on 24 July 2014 (www.responsibleresearch.graduatecenter.uni-muenchen.de/index.html). The lecture is broken into two parts, the first one dealt with biomedical publishing, its origins and current state. This is the second instalment on solutions. Videos of both the lecture and the subsequent panel discussion are available at www.responsibleresearch.graduatecenter.uni-muenchen.de/presentations/videos/index.phpÂ

The problem is, to a certain degree, clear. Let me recap. What was conceived as a way to communicate between scientists and between scientists and the public has become a measure of success, a ruler of quality and an arbiter of professional development. The change in character has altered what science is, how it is done and how scientists are evaluated; too many papers, difficulty of separating the wheat from the chaff, limited funds….Nowadays to do good science is not good enough. To survive in science one needs skills like being able to ‘sell’, being a good story teller, being able to chat up editors, being savvy on more than the subject matter, and then combine these skills to get money. Furthermore an increasing blur between data and thought, between science and accounting creates a climate of confusion in which money talks. Spin and good PR are as important as deep science and enquiry. And an important reason for this is that what we are working with is a XIX century system that has never adapted to the times. What we have, as I have said before is a collection of XVII century tulip bubbles about to burst –the glamour journals- sustained by a few. But there is change coming (I think) and we need to support it and make it grow. Here are what in my view are the important elements that are leading this change

First, Open Access. This is a most important development and one that for the most part has achieved its goals. You have heard a great deal about this so I shall not dwell on it. Open access is a natural response to the attempt of several publishers to own your/our work, to the fact that science has become a business for the journals but it is our toilings that they work with. Open access is not free publishing but it is rational and sensible publishing and it is good to see that funders of science have rallied to support this move. Everybody should publish Open Acess. While everything is good here, we should not lose sight of the fact that the big publishers have seen the goose of the golden eggs and have rallied to produce their own Open Access journals that take advantage of their brand names to make more money. And this takes me to the next all important issue New Journals

Partly because of the publishing niche opened up by Open Access, partly because of the increasing demand for space to publish driven by an exponentially increasing output, new journals emerge every month. Do we need them? How do we decide where to publish? Are these journals changing anything or are they mere derivatives of what we already know? The latter is often the case and clothed with the mantle of Open Acess there is a barrage of faked and real journals which tempt us with more or less success.

There are however positive exceptions which are actually trying to move away from traditional models and aims. At the forefront is a new journal called eLIfe; you have heard about it earlier today. It is an online only journal with much to be commended for. I am particular fond of their reviewing procedure and many technical aspects of how papers are presented, the kind of discussions it posits and the support it has from three heavy weights of research funding (Wellcome, Max Planck and HHMI) which makes it a statement of intent. It is a scientists journal which is trying to carve the future. But…….they have a problem, namely that the people who run the journal are the same people that brought us Cell, the rightly maligned impact factor, who review and publish in Nature, Cell and Science and who control where you publish, how you publish and whether you get a grant or not. How can you implement change with the people who created, and still favour, what you want to change? I guess the answer is with difficulty. Furthermore, they promote openness and yet, many letters of rejection are signed by their chief scientific editor, Randy Shekman, independently of the field, because the editors in charge want to remain anonymous. This is not a good advertisement, But remember what I told you, most of the people behind the journal are the same ones who have created the problem that eLife claims to want to solve. So, while I applaud what they want to do, they still have work to do. Also, the stated aim of the journal is to compete with the glamour journals, but to do so in a fair manner, by attracting quality. But here we hit another problem and this is the difference between quality and cool and eLife, inevitably, is so far a mixture of the two with a heavy dose of cool. But I do not want to knock them down because they have much riding for themselves and have an opportunity to do something transformative and help us move forward. Take these comments as a recognition of their toilings and their openness to new ideas. They can succeed but they need to be bold, really bold and not fall sleep in their coolness. And it is for us to make sure that they deliver.

I mention eLife because it is, in my mind, the most interesting project but do not forget others. Most interesting amidst these, the loved and hated PLoS ONE which, as anybody who has published in it knows, is not just a place where you pay and publish (there are many of those). It is a serious journal in the spirit of publishing sound, rather than soundbite, science (notice the irony! I have often heard as a criticism of PLoS ONE that it ONLY wants to publish sound science……….). Sure it is a mixed pot but I have never had a paper published there without proper revision and their acceptance rate is around 70%. It is a pioneer. Other journals have emerged as derivatives of mainstream products and thus the Company of Biologists have Biology Open and Nature and Cell Press continue to expand their portfolio to fill their pockets with Open Access journals. So, the choice today is very large. My advice here is simple: publish where you feel it is more appropriate. Do not waste your time in the lengthy and morale-sapping process of peer review in the glamour journals. It is not worth it and certainly not worth your time. And yes, wherever possible use scientist based journals.

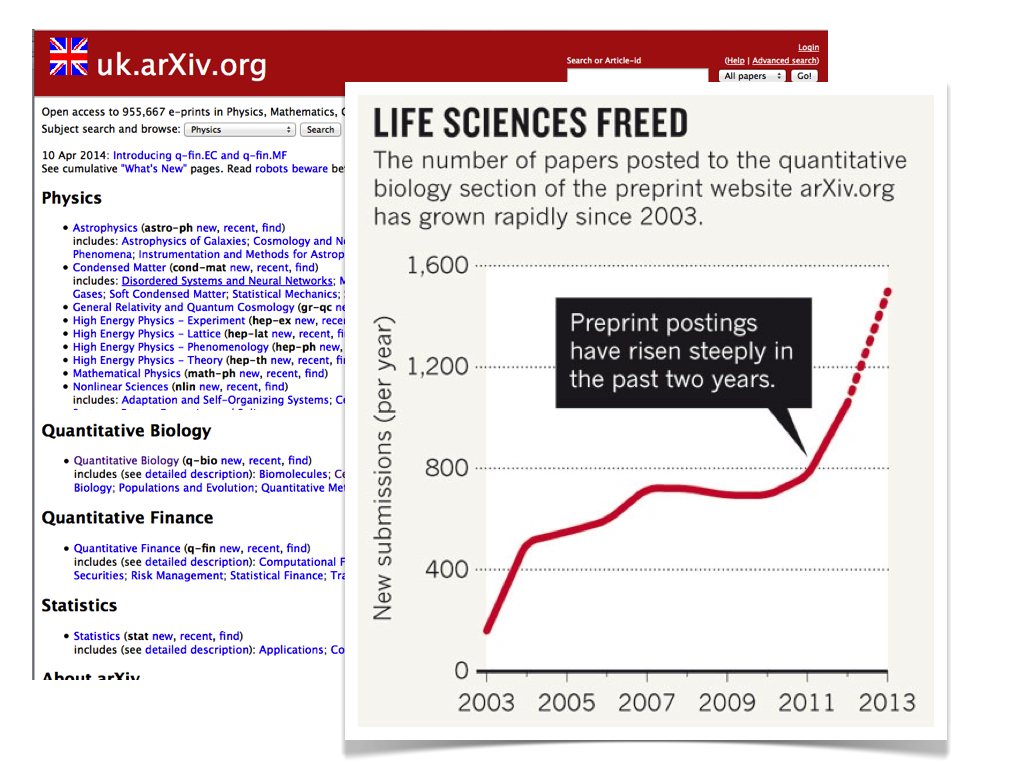

One interesting development in terms of ‘new publications’ is the emergence of preprint servers. This is a notion that comes from the physicists’ arxiv (http://uk.arxiv.org/), which has been running successfully for over twenty years (founded in 1991). In fact arxiv represents the main avenue for publication of new findings for the physics community and they do not worry too much about impact (the biosciences flavour); what they worry about is precedence and being read and discussed. How does it work? When you have results that amount to a manuscript, you prepare them and post in arxiv; you get a doi and you wait for comments or simply mature the work (you can upload new versions of the manuscript). In the meantime people can see the paper. Then when you think it is ready for ‘official’ peer review, you submit it to a journal, and most journals, including Nature and Science, accept papers that have been posted in arxiv (http://en.wikipedia.org /wiki/List_of_academic_ journals_by_preprint_policy). There are good reasons for this: Nature and Science are journals where physicists publish, as arxiv is a central element of communication for the physics community, Nature et al have to accept the rules of their game. A lesson here: Nature and Science have to accept the rules of the scientists and notice that Cell press does not like arxiv. There must be a good reason for this: it is a publication. Over the last few years, biologists with a more quantitative inkling have begun to use arxiv, and this has led to a new section in the journal on quantitative biology. As a response to this interest of biologists in using arxiv, and as a way to rally the more traditional biology community, a few months ago BioRxiv (http://biorxiv.org/) was launched, a biological version of arxiv. It is working well, has not yet gathered momentum, but it hails a cultural change and I very much encourage you to use both arxiv and bioRxiv. There are other preprint servers, as they are called e.g PeerJ, Figshare and F1000. So, again, you have a choice.

One interesting development in terms of ‘new publications’ is the emergence of preprint servers. This is a notion that comes from the physicists’ arxiv (http://uk.arxiv.org/), which has been running successfully for over twenty years (founded in 1991). In fact arxiv represents the main avenue for publication of new findings for the physics community and they do not worry too much about impact (the biosciences flavour); what they worry about is precedence and being read and discussed. How does it work? When you have results that amount to a manuscript, you prepare them and post in arxiv; you get a doi and you wait for comments or simply mature the work (you can upload new versions of the manuscript). In the meantime people can see the paper. Then when you think it is ready for ‘official’ peer review, you submit it to a journal, and most journals, including Nature and Science, accept papers that have been posted in arxiv (http://en.wikipedia.org /wiki/List_of_academic_ journals_by_preprint_policy). There are good reasons for this: Nature and Science are journals where physicists publish, as arxiv is a central element of communication for the physics community, Nature et al have to accept the rules of their game. A lesson here: Nature and Science have to accept the rules of the scientists and notice that Cell press does not like arxiv. There must be a good reason for this: it is a publication. Over the last few years, biologists with a more quantitative inkling have begun to use arxiv, and this has led to a new section in the journal on quantitative biology. As a response to this interest of biologists in using arxiv, and as a way to rally the more traditional biology community, a few months ago BioRxiv (http://biorxiv.org/) was launched, a biological version of arxiv. It is working well, has not yet gathered momentum, but it hails a cultural change and I very much encourage you to use both arxiv and bioRxiv. There are other preprint servers, as they are called e.g PeerJ, Figshare and F1000. So, again, you have a choice.

Why use Preprint servers? There are many reasons and I have discussed the matter before ((http://amapress.gen.cam.ac.uk/?p=1239) but here you have two which should be of interest to you. One, because it gives your research quick visibility and establishes precedence. Two, because it gives you a doi and with it, the ability to refer to it in applications and also in papers. As I say, this is the bread and butter of the physics community and I do not understand why it should not become ours.

Why use Preprint servers? There are many reasons and I have discussed the matter before ((http://amapress.gen.cam.ac.uk/?p=1239) but here you have two which should be of interest to you. One, because it gives your research quick visibility and establishes precedence. Two, because it gives you a doi and with it, the ability to refer to it in applications and also in papers. As I say, this is the bread and butter of the physics community and I do not understand why it should not become ours.

And publication rolls on to the next topic, an all important modern classic, Peer review, which echoes much of what I have said in the first part, so I shall be brief. Few people would disagree that peer review in the biomedical sciences is in crisis and changing it should be the next target of our community after Open Access,. Peer review is not doing the job that it is supposed to do. At the moment, the main role of peer review is to make it difficult for you to publish and the degree of difficulty is proportional to the perceived glamour of the journal and, in the journals where this index is high, inversely proportional to your interactions with editors and members of the editorial board. Remember the remarkable advice from the Cell Press editor I mentioned earlier. Anybody who believes that peer review does a good job is dreaming. Please do not think that I do not want peer review. Nothing further from the truth but, I do not want a surrealistic process which has so much element of chance and cliquishness.

There are no easy fixes here. The peer review is the community. We do need peer revew, but we need a system which avoids the extended essays and legal arguments which bedevil the system at the moment. The longer you are in this business, the less you trust the system. These days the collection of reviewer’s comments and replies can be longer than the paper itself! Some journals, like EMBO J and eLife have interesting leads that should become common practice: one, and only one, round of review (both of them and extending) and, in the case of eLife, comments reduced to 500 words (one page, if you want to be generous). There is no reason why one needs more space to assess a paper. A review is not about the paper the reviewer would like to write with the data and resources of the reviewee, but simply a comment on the paper. You will soon see what publishing a paper in a glamour journal means and you will not like it. Perhaps the worst thing about the process is the number or unnecessary experiments and their cost which do not advance the paper (on this see the almost classic : http://www.nature.com/news/2011/110427/full/472391a.html). A few comments and an editorial decision is what should happen. As we have seen this is what it used to be and maybe we should go back to go forwards. I wish the examples of EMBO J and eLife would be followed.

Then there is pre- and post- publication peer review. This is, like anything to do with this issue, a huge subject so I shall summarize. Many people advocate for postpublication peer review and to a large degree this goes on, in private, at lab meetings, tea rooms, discussions at meetings. But there is no will to do this openly. Most journals have now, routinely, places for comments which are not used. As we heard earlier: why are happy to write an impromptu review of a restaurant, a hotel or a book but we cannot do it with a piece of scientific work? What is wrong with bioscience? The only public comments that are allowed are positive. It seems to me that the notion and escalation of anonymous peer review has much to do with this situation. What we have is fear of backlash from criticism. The STAP case is a good, positive example of the cleansing power or open discussion of results. There is also a case for prepublication peer review but for these there are venues: preprint servers. As usual, for all the talking what happens is less than what one might expect. Preprint servers are not bursting at the seams. Lots of talk, but less action. The reason is because, for the most part, the scientists that make this tick are sensible and to prepare a manuscript takes time and care. The so far limited use of those servers, and the limited interest of bioscientists in them, should also be food for thought but, in any case I repeat my advice: use them!

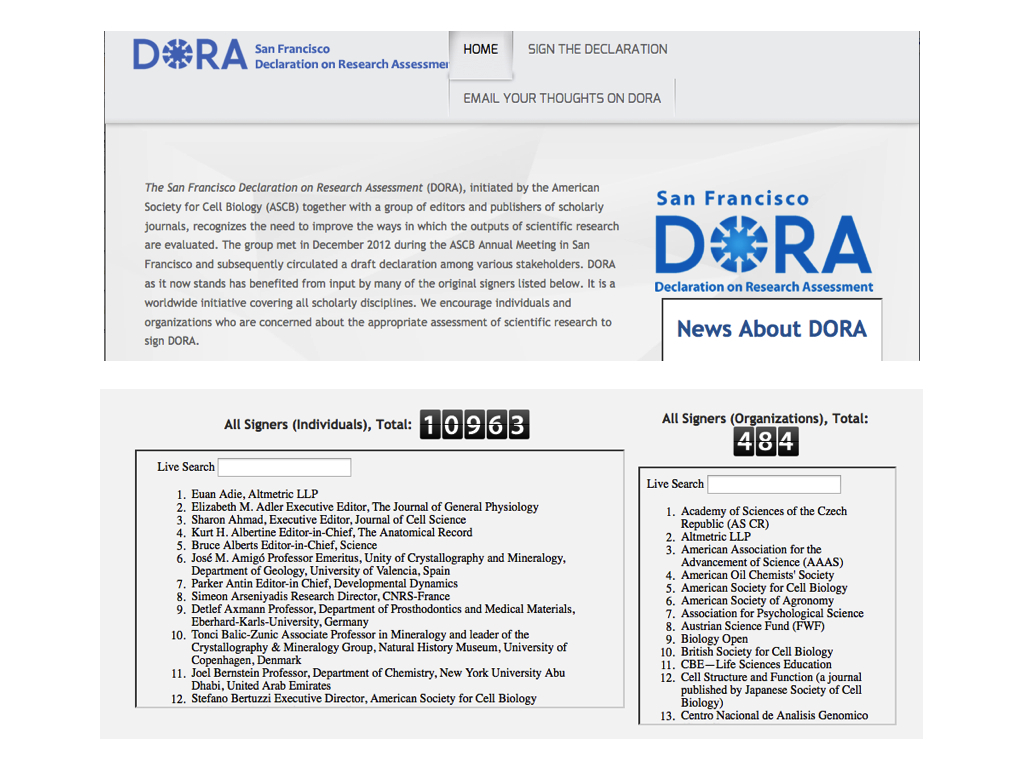

And, of course, we need peer review. But we need to recover some sanity. We need responsible editors who do not fall prey to the endless sequence of reviews which cost money and careers, and we also need sensible reviewers who understand what reviewing a paper is and, especially, that it is not a way to block a piece of science seeing the light. We need to remember what a scientific article is and remember that it is the work that matters, and if you want to see more of the future let me tell you about another important development: San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (SFDORA or DORA for short).

And, of course, we need peer review. But we need to recover some sanity. We need responsible editors who do not fall prey to the endless sequence of reviews which cost money and careers, and we also need sensible reviewers who understand what reviewing a paper is and, especially, that it is not a way to block a piece of science seeing the light. We need to remember what a scientific article is and remember that it is the work that matters, and if you want to see more of the future let me tell you about another important development: San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (SFDORA or DORA for short).

In 2012, at the annual meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology, a group of publishers and funders signed a declaration, SF DORA, in which there is an explicit statement for “a pressing need to improve the ways in which the output of scientific research is evaluated by funding agencies, academic institutions, and other parties†(http://am.ascb.org/dora/). The main point that DORA wants to press home is that people should be judged by what they publish and not where they publish. To date the declaration has been signed by over 10,000 individuals and over 400 institutions. My advice is sign and, more importantly, enforce it. Make sure that those who have signed it, abide by it. What DORA says is obvious and it is surprising that it needs to be said.

And so to the future

The point of this lecture was to discuss publishing in the biosciences, why you might want to publish, what you would like to publish, how would you like to publish it and also where to publish. We have seen that answering these questions is more complicated than you think at first sight. There are two main reasons for this, the first one is that publishing today is not just a way to reveal and share our work but rather a complex action which will impinge on our future and job prospects, and one that is not straightforward. Together with this there is the fact that, in contrast with the science itself, the structure of scientific publishing has not changed much over the last hundred years and that therefore we are working with a system which is not only overloaded, in terms of supply and demand, but also, simply, not fit for purpose. As a consequence of this and, really, because of the impact where you publish has on your career prospects, there is a very open debate and scrutiny of the publications system and associated issues. There are many ideas around as to how to change it, and change is happening –slowly- but it is happening. So, where is all this going? To predict the future is always difficult but to close I would like to enumerate a number of elements of the tangle which need to be addressed for change to happen

1.The system of assessment of our work by the journals has to change. The way papers are reviewed by editors and reviewers and the roots of high rejection rates need to be reviewed. Some creativity and leadership is needed here and I would suggest that eLife and EMBO Press have made interesting steps in the right direction about this.

In this context if a reviewer wants to have an extended discussion with the author i.e exceed a certain length in the review, and suggest new experiments (which mean money), the identity should be revealed and the author of a manuscript should be able to have a proper discussion of what is being suggested to see what is reasonable. Like many I suspect that having to reveal the identity will change the tone and the content of the review.

2. Journals should implement seriously their policies of ‘conflict of interest’ and at this, they should make sure that their editorial boards do not have members that are also in multiple editorial boards of competing journals. This will ensure a commitment of the editorial board members to the particular journal and will, also, expand the group of people that make decisions about the content of those journals.

3. The journals have to adapt to the times. Supplementary Material was another added on to the operating system and as could have been predicted, it has got out of hand. Journals like Nature and Science now publish incomprehensible short papers where the actual science is in the supplementary. The reason why the text of many of these papers is gibberish is because it has been fragmented in the reviewing and publication process. Journals need to find new ways of conveying the science and a way to normalize the size and content of a paper i.e they need to adapt to the times.

4. Science is made by the scientists and it is for the scientists. There is a trend, promoted in particular by Cell Press, of dumbing down the science, of favouring impact and headline over content. Of favouring certain authors who frequent meetings and editors. Pieces of research become stories and journals rather than reporting advances, tell stories about genes and proteins and it is how you tell a story, rather than the content, that begins to matter. This could not happen in Physics but biology lends itself to this (and if you don’t believe it remember Rudyard Kipling’s ‘Just so stories’ some of which, with added materials and methods, could work well in Cell Press.

Journals need to take us seriously, we need to take the journals seriously.

5. If journals, particularly the generalists, want to keep their clout, they have to be more stringent on how they choose and train their editors. Teaching how to be an editor rather than learning it on the trot should be compulsory. In an increasingly professional world it is surprising that the main qualification to work on those journals (Nature, Science, Cell) is not to like, be bored with or have shown inability in the subject matter they are going to decide on. Imagine that the main reason to become a Chef is that you are bored with cooking or do not have a palate…… There should be a form of professional qualification for scientific editors e.g a masters on the subject (maybe there are). The consequences of the way editors are selected are clear for all to see. This can and should change.

But in the end, and for change to happen, WE have to make choices. At the moment we have chosen to emphasize form over content and science has become a routine mixture of salesmanship and one-upmanship, a power game where a few have an advantage. There are lots of meetings and lots of papers, but (with some exceptions) very little discussion and certainly open discussion. In public, all papers are great, all findings are exciting and there are lots of breakthroughs. In private, the picture is different. Part of the reason for this is that we have substituted questions and science for data presentation and therefore there is little conceptual to talk about. There is also the problem, allow me to emphasize, that the journals that drive the most visible biosciences are run by people that are inexperienced at both science and publishing. My advice is always, to avoid those journals. As long as we continue to search for their endorsement as a proxy for scientific quality, we shall be delaying change and we shall continue in a path towards forgetting the heart of the scientific quest.

The future belongs to you, so: make sure that you see it before it catches up with you. Nowadays the form of science is as important as its content and for this reason you should make sure that you shape it, that you don’t let the shaping to others. Open Access has become normal, let us make sure that other aspects that need change also become normal. Move away from glamour journals and towards journals that are led by scientists, use preprint servers, be open, careful and mindful when you review papers and grants (don’t do a review that you don’t want to see yourself), implement DORA. Let us make sure that science gets back to a normality adapted to the times.

PS: I was about to post the second part of the lecture when I heard the news of the suicide of Y. Sasai. This needed some pause and reflection. To many of us who worry about the current trends in the biosciences, the STAP affair has highlighted much of what is wrong about our enterprise and this is why I dedicated a part of the lecture to it and so did some of the other speakers. Whatever happened and whatever the reactions and possible consequences nobody would have thought of this end (so far) because a human life, and the blurring of a tremendous scientific reputation built over years of hard work, is not a prize to pay for the search of notoriety gone awry. Reflecting on this we should also remember that the chase of a publication in Nature, Science or Cell has many casualties we rarely hear about in the form of careers, enthusiasm, personal lives….while science was at the heart of the STAP affair, it was the search for the limelight that was its Achilles heel and, of course, Nature was only too happy to collaborate. Their job is to sell their product. It would be good if, as a community, we would think about how this came about and take corrective measures because otherwise our endeavour will lose its meaning, if it has not lost it already.

Additional miscellaneous reading

Kreiman, G. and Maunsell, JR. Â Nine criteria for measuring scientific output. Front Comp Neurosci.5, 1-6.

Pulverer, B. (2010) Transparency showcases strength of peer review Nature 468, 29-31

Segalat, L., (2010) System crash EMBO Reports 11, 86-89.

van Dijk, Manor, O. and Carey, L. (2014) Publication metrics and success in the academic job. Â Curr. Biol. 24, R516

Vale RD. Evaluating how we evaluate. Mol Biol Cell. 2012 Sep;23(17):3285-9.

Vosshall, L FASEB J. 2012 Sep;26(9):3589-93. The glacial pace of scientific publishing: why it hurts everyone and what we can do to fix it.

Williams, E., Carpentier, P. and Misteli, T. (2012) Minimizing the “Re†in Review.  J Cell Biology 197, 345-346.

“an increasing blur between data and thought” – that’s a good point, and a worrying one. Just in the past weeks I have seen multiple cases of papers cited wrongly, mostly because “Fig 8” seemed to have been mistaken as fact rather than hypothesis.

Potential over-/abuse of storytelling and -selling is something graduate students are actively taught in nowadays (and may have been for a long time, I don’t know). So it’s not just the journals that need to change their attitude, it’s also the universities.

Abandoning glamour journals seems like a noble idea, but one only hears established scientists talk about it (who, very often, have had an above average share of said glamour). Until the people who give out funding, jobs and tenure actively select against it, I can’t see how anyone trying to make “it” will be convinced (sadly). (interestingly, these journals seem to be much less valued in mathematics)

Alfonso, the evolution of publishing has indeed changed quite radically over the years but for many years was driven by publishers rather than science itself. Indeed, the only input scientists had was via the editorial boards of journals and there was a lot of lip service paid to that advice. We tend to forget the transition to on-line access, the reprint request postcards, the library binding of last years issues, etc. I do agree that many of the most interesting (but not all) recent developments in publishing have emerged from scientists. I seriously doubt Open Access journals would have emerged from the established publishing houses without the impetus of the efforts of the PLOS founders (although a tip of the hat to Vitek Tracz, a rather adventurous publisher). I also think that many journals do value the scientific integrity and knowledge of their editors. The fact is, once out of the world of actually producing new research, it is very difficult to maintain that direct knowledge-base and so people become more reliant on others to tell them – through symposia, etc. – what is important. This is the root of trends in research, the hot topics and bandwagons. It’s self-fulfilling and sustaining. Once a topic has been published in a CNS journal, it attracts more of the same. There are strong incentives to coalesce towards areas that are seemingly hot – for publications, funding and profile. So we play.

The bigger question is why do journal hierarchies exist? Is this simply a hang-over from times when we had to be judicious about which journals our libraries could afford to subscribe to? Have we become lazy? Or is there still value in “curation”? If the latter, then it would seem we perhaps still have someway to go in breaking down access barriers and developing better tools for locating studies of interest and in broadcasting/advertising when a study should be of interest to others. In theory and especially with on-line access, there is absolutely no reason why a paper published in one journal should have any more impact in a similar paper published in another. The choice of where to publish should be based on suitability and process.

I think they hierarchies still serve a curation purpose. There are interesting tools now like Google Scholar recommendations and Pubchase (www.pubchase.com) that try to provide automated personalized recommendations. Until these are very good and common place we will continue to need proxies for quality. Judging individual works by where they are published is a very bad estimation but there is a sea of things to read and we need some way to deal with it. I have been saying for a long time that the best way to do away with the hierarchies is to build good recommendation systems.

The curation aspect of glamour journals is fairly irrelevant to someone like me who has not known a time before articles were available online. I find papers based on key word searches in Google Scholar et al., by following tries of citations and recommendations. Links within a particular journal’s website play only a minor role, and there are journals who seem to do as good or a better job at it than NCS.

Granted, when searching for papers the ones with the most citations still come out top, which might introduce a bias towards glamour.

I agree, Jim, in the current sea of stuff it is sometimes difficult to navigate and the glamour journals provide a compass which increasingly is not working because it serves their interests and not ours. Difficult to know where it is all going but Open Access is an example that things, good things, happen.

To try to gain some sanity by avoiding glamour journals is not a noble idea, it is a rapidly increasing necessity. One such publications will, maybe, get someone an interview but I am not sure that it will get that person a job unless it is accompanied by good science. The latter is only achievable through individual quality. I do see the point that it is easy for people who have made their careers on the back of such publications to say ‘abandon them’, but the fact is that, for the most part it is not those people who are encouraging the move but a large majority, usually mid career scientists, who have seen the danger of continuing to promote those journals. If we all do it, things will change.

Scientific publishing is on the move, has only been on the move, and as I said in the lecture, we all have to make an effort to break the status quo and develop a system in tune with the times.

You make a good point ob getting the interview vs. getting the job, one that I would like to believe. However, I still hear from biologists that are told (or fell like) they have to get a CNS to get tenured. Of course it’s university dependent and hopefully it’s on it’s way out, but in the short- to mid-term I can still see that as an inhibiting factor for our glamour cold turkey.